Turning Conflict into Rhyme: King’s Team Studies Reconciliation in Belfast

Led by Dr. Anthony Bradley, eight King’s students studied peace and reconciliation in Northern Ireland at Stranmillis University College, Queen’s University Belfast.

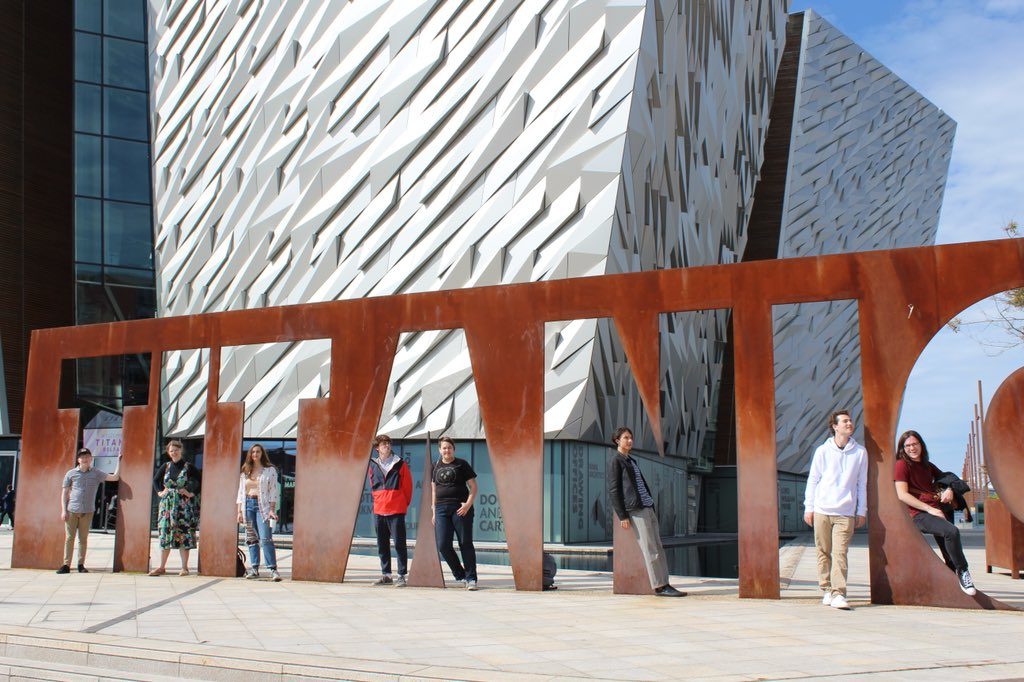

In June, Dr. Anthony Bradley and eight King’s students traveled to Belfast, Northern Ireland for a course in Peace and Reconciliation offered through Stranmillis University College of Queen’s University Belfast.

From June 16-30, the students—Sara Atha, Julia Campoli, Luke Chambers, Caitlin Coats, Jackson Kane, Graham McNally, Tanner Sanderford, and Nolan Wolfe—heard from Stranmillis faculty and many guest speakers, including local historians and politicians; church, police, and community leaders; and journalists, artists, and musicians. The group also visited historic sites like the Museum of Orange Heritage, the Belfast Peace Walls, and the 400-year-old Derry City Walls that overlook the site of the 1972 Bloody Sunday events.

“Sometimes you have to leave the U.S. to really see why everything we do at King’s matters,” says Bradley, who facilitated and supervised the trip. “Northern Ireland is the perfect place to study the intersection of all of the majors at King’s. You study the politics, religion, art, and literature of a culture that has experienced a lot of conflict, but you also see how those exact same disciplines have been used to provide hope and reconciliation for the purposes of human flourishing in Northern Ireland.”

As one example, students heard from Northern Irish artist Ross Wilson, who has participated in community reconciliation efforts by painting over paramilitary murals. One such mural formerly portrayed a gunman in a ski mask (depicting a member of the UFF, a group that killed hundreds during the Troubles). In its stead, Wilson painted a new portrait of “King Billy” William III. Wilson said that he sees his work as taking the hurt from what people have done and transforming it. Wilson takes physical monuments of pain and turns them into images that “portray that existing hurt as a memory that you associate with healing,” says Jackson Kane (PPE ’20), turning conflict into “rhyme.”

Students were especially moved by their visit to Belfast’s Peace Walls, which still separate communities divided by religion and politics. “The idea here was to separate neighbor from neighbor in order to ease the conflict and stop the pointless deaths,” Julia Campoli (MCA ’19) says. “It was just astounding to me that that was even necessary: that you would need to separate two people from within the same city who live such similar lives.” Even today, if you ask a Protestant kid to draw his neighborhood, he won’t know that the Catholic side of the city exists, Jackson adds.

Other visits included a tour overlooking the Bogside area of Derry, where Bloody Sunday took place. Their tour guide’s father had been killed in the massacre.

Students also heard from many notable political leaders, such as Professor Monica McWilliams, co-founder of the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition and participant in negotiations that produced the 1998 Good Friday agreement, and Daniel Lawton, U.S. Consul General in Belfast.

“The U.S. Consul General talked with us about career and vocation, helping the students to understand the pathway to working in the foreign service,” Bradley says. “Dan Lawton said that the three disciplines that really make a good diplomat are politics, philosophy, and history. I sat there and smiled to myself because this is what King’s students are doing as normal. It just goes to show what King’s is doing to prepare students for opportunities through the way we organize our curriculum.”

Caitlin Coats (MCA ’20) says, “We heard from researchers, reporters, politicians, artists, historians, priests, social workers, and more. All of these individuals were at the top of their field and extremely passionate about the work they were doing. Even though they came from a variety of vocations, each was doing their part to bring healing to Northern Ireland. I tend to get overwhelmed at the amount of problems in this world, but the most effective way to solve those problems is by focusing on the particular work God places before me.”

Students earned three credits from Queen’s University Belfast for the Peace and Reconciliation course. Besides daily lectures and site visits, the course required each student to read a series of scholarly books, write a paper, and deliver a 10-minute presentation applying lessons from Northern Ireland to conflicts in the United States. Students addressed racial divisions in the United States and proposed ways that polarized and tribal political parties could work together for the sake of their communities. Bradley says, “Administrators who sat in on that session were blown away by our students’ ability to assess the situation in Northern Ireland and make applications to situations of conflict in America.”

Stranmillis University College faculty members Dr. Barbara McDade and Dr. Sharon Jones helped to envision and propose this partnership between Queen’s University Belfast and The King’s College. Plans are in place for a second Belfast trip in the last two weeks of June 2019, and details will be finalized this fall.

For Bradley, the most rewarding part of the Belfast trip is seeing students develop their understanding of the world. Pointing to violence and rioting in Derry that has recently been in the news, Bradley says, “There are now eight students who can explain the historical context of current events in another part of the world, because they were there, they saw it, and they talked about it with people on the ground. As a professor, it’s encouraging and empowering. It makes me want King’s to have more trips like this, to expose more students to the world, so they can really get a sense of what’s happening in the world in which they live.”