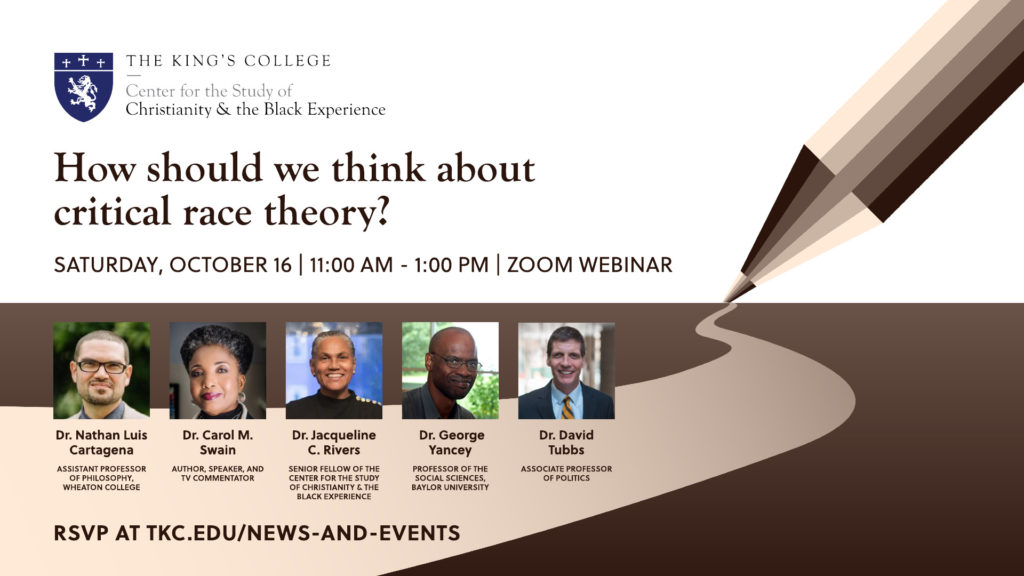

How Should We Think About Critical Race Theory?

Dr. Jacqueline C. Rivers and Dr. David Tubbs of The King’s College joined Dr. Nathan Luis Cartagena of Wheaton College; author, speaker, and TV commentator Dr. Carol M. Swain; and Dr. George Yancey of Baylor University to discuss Critical Race Theory.

On October 16, the Center for the Study of Christianity and the Black Experience at The King’s College hosted a panel discussion on “How Should We Think About Critical Race Theory?”

Moderated by Dr. David Tubbs, associate professor of politics and director of the Center for the Study of Christianity and the Black Experience, the virtual event featured presentations from a diverse set of experts including Dr. Jacqueline C. Rivers, senior fellow of the Center for the Study of Christianity and the Black Experience; Dr. Nathan Luis Cartagena, assistant professor of philosophy at Wheaton College; Dr. Carol M. Swain, author, speaker, and TV commentator; and Dr. George Yancey, professor of sociology at Baylor University. The event aimed to provide clarity about what Critical Race Theory is, to discuss how Americans should think about it, and to examine if the central elements of the theory are consistent with the truths of Christianity.

WATCH: Full Panelist Presentations and Q&A for “How Should We Think About Critical Race Theory?”

Tubbs opened the panel discussion with a brief explanation of the origins of Critical Race Theory (CRT) in the American legal system during the 1980s. He noted the popularity of CRT in contemporary discourse, and the lack of a definitive definition. To provide clarity, Tubbs introduced the four panelists.

Cartagena began his remarks by affirming the vexing nature of a discussion about CRT due to the lack of a clear definition. He shared quotes from Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the term, and Tom Curry, professor of philosophy and Personal Chair of Africana Philosophy and Black Male Studies at the University of Edinburgh, illustrating the indiscriminate use of the term CRT in academia. Outside academia, Cartagena pointed to Christopher Rufo, director of the Initiative on Critical Race Theory at the Manhattan Institute, who claimed bestselling authors Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to Be an Antiracist, and Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility, use the CRT moniker to “…advance a culture war.” Cartagena raised a second reason the discussion of CRT is challenging: a question like, “How should we think about Critical Race Theory?” contains assumptions. To whom does “we” refer? All people? U.S. Christians? Christians of the African diaspora?

Cartagena then provided structure for the discussion by defining CRT, breaking down the concept, and describing the intended audience. “CRT is a legal movement aimed at understanding, resisting, and remediating how U.S. law and legal institutions… have fostered and perpetuated racism and white supremacy.” To further clarify, he first explained that CRT proper 1) began in legal studies 2) houses multiple and competing traditions and theories and 3) employs multidisciplinary methods and source material. Secondly, he discussed and gave examples of the academic derivatives of CRT as it “…travels into other academic disciplines such as education and philosophy.” Third, he discussed CRT’s involvement in today’s culture wars.

Cartagena concluded by providing two truths to guide how Christians should think about CRT. First, “we should affirm that God is the ultimate source of all Truth. For us, all Truth—even extra-biblical truth—is God’s Truth.” Second, “we should affirm that everyone thinks through metaphors.” As a means of thinking about the extra-biblical truths in CRT scholarship, Cartagena uses historical examples to suggest we “turn philosophical water into theological wine.”

Swain began her presentation arguing that CRT is one of a number of critical theories that divide people (e.g., gender theory, colonialism theory, feminist theory). CRT in particular divides people into “white oppressors” and “minority victims.” “CRT as I understand it,” says Swain, “operates very much like a religion because white people are expected to confess that they are racists regardless of whether their ancestors were abolitionists or people who risked their lives setting up the underground railroad.”

Swain discussed the negative effects of CRT on K-12 students, specifically mentioning ethnomathematics, “…in which the case is made that math is racist and that different cultures can get different answers to mathematical equations and problems.” She pointed to the message CRT sends young people that being on time, working hard, sitting quietly in class, and planning for the future is “whiteness.” And for those students who push back, Swain referred to reports of bullying and shaming.

Swain said, “I see CRT as the number one civil rights issue of our day.” She asserted that CRT’s effect on society is un-American, unconstitutional, and contrary to civil rights laws. She went on to share strategies for fighting back from her book Black Eye for America.

Rivers began her presentation listing the five basic tenets of CRT as outlined in the writings of two key scholars in the CRT movement, Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic. She focused her remarks on two of the five tenets—“racism is normal” and “racism is a social construct.”

With regard to the tenet “racism is normal,” Rivers noted the sweeping nature of the phrase, saying, “It’s not the same as saying every single white person is born with racism in their DNA—that is simply not true.” Rivers shared academic studies demonstrating how prejudice appears within societal systems, rippling into employment, the American criminal justice system, where people choose to live, and what each of these factors mean for a family’s education and advancement.

To demonstrate race as a social construct, Rivers referred to studies that found despite differences in physical appearance, “there is no biological basis for race or clear biological markers for different races.” She continued to build her argument by recounting the Census Bureau’s evolving collection of assigned racial data versus modern self-assigned categories, and the role of government policy that created the wealth gap between Black and white families as a result of the New Deal in 1933.

Rivers concluded with a critique of a concept promoted by CRT—namely, the idea that racism is permanent. Citing the morphing reality of racism, she points to statements by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic that acknowledge changes that have already happened. “As Christians, we have a responsibility to distinguish between what CRT scholars claim and what their critics say is in fact CRT.” She reminded the audience that as Christians, “we have a responsibility to weigh these ideas—where they are speaking truth and to reject the errors.”

Yancey began his presentation outlining the arguments against CRT (i.e., that it is anti-white, doesn’t tolerate disagreement, distorts history, creates animosity, etc.). Yancey went on to show how elements of the CRT controversy are based on a “mythology” of CRT rather than what it actually is. Yancey outlined “a better way” that does not silence white or Black audiences and that moves beyond polarization to community and more collaborative conversations.

The Q&A period provided additional time to pursue ideas presented by the four panelists. The questions raised included, Are some American whites reluctant to engage Critical Race Theory because doing so requires attention to the history of race relations in the United States? Are white Christians today more or less willing to think about questions of racial justice than they were 30 years ago? Should American public schools be receptive to teaching Critical Race Theory to their students?