Dr. Paul Mueller Challenges Conventional Wisdom about the 2008 Financial Crisis

On February 15, Dr. Paul Mueller delivered a lunchtime lecture on his book, 'Ten Years Later: Why the Conventional Wisdom about the 2008 Crisis is Still Wrong.'

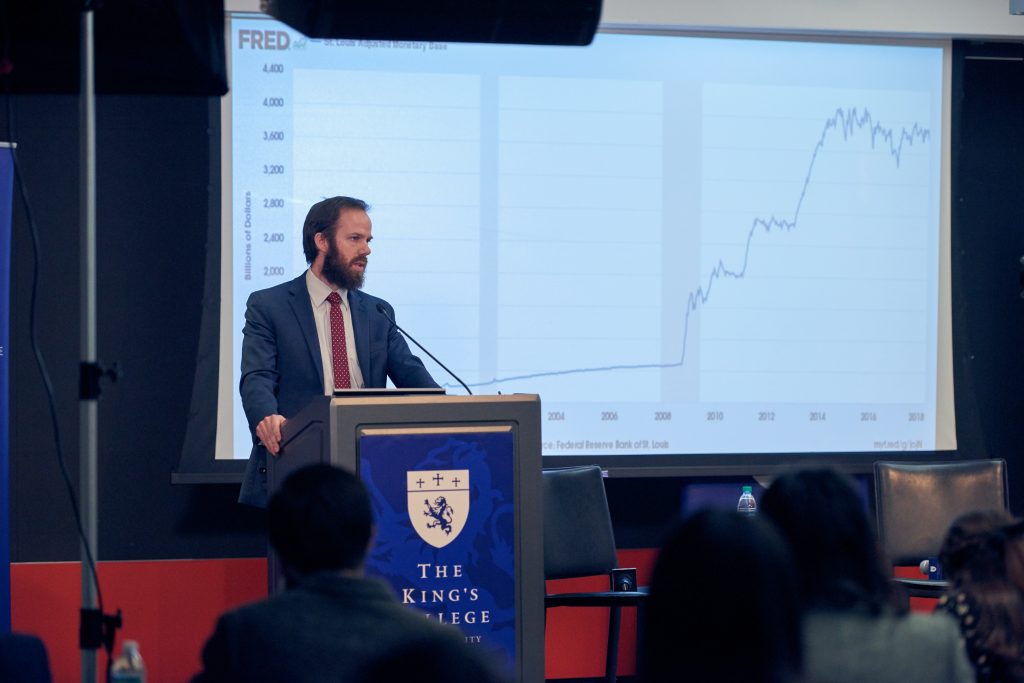

Above: Dr. Paul Mueller described how in 2008, the entire financial system was linked with the strength or failure of the housing market.

On Friday, February 15, Dr. Paul Mueller delivered a lunchtime lecture on his recent book, Ten Years Later: Why the Conventional Wisdom about the 2008 Crisis is Still Wrong. After presenting the main claims of the book, Mueller extended the conversation through a discussion with David Bahnsen, a member of the Board of Trustees and founder of The Bahnsen Group, and a short time for audience questions.

“Dr. Mueller’s command of economic data and economic history was powerfully on display at his book launch for Ten Years Later,” said Dr. David Innes, chair of the program in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics. “As one who was in the housing market during the 2008 collapse, I found that his account of the Great Financial Crisis brought much to mind but much more to light. His book is a welcome corrective to popular thinking on the subject and sober counsel on how to avoid another crisis of this scale.”

WATCH: Dr. Paul Mueller’s Ten Years Later book launch

Mueller began his lecture by explaining how, in 2008, the entire financial system was linked with the strength or failure of the housing market. He described how banks sold mortgages to enterprises such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which then pooled the mortgages and sold “shares” to the pool called mortgage-backed securities. This “spread the risk throughout the financial system in the U.S. and the world,” Mueller said. Once the housing bubble popped, default rates on mortgages started to soar, which created significant declines in the value of mortgage-backed securities and thereby significant losses for banks. As losses mounted, large U.S. banks began to reduce their lending to businesses throughout the economy, leading to job losses and a recession.

Another aspect of the crisis involved the fact that banks were “highly leveraged,” taking on large amounts of short-term debt with relatively little equity or capital. Banks would borrow funds for a period of months or weeks, pay some interest, and then renew the loan when it came due instead of paying it back in full. “It was cheaper to borrow at that rate and lenders felt it was safer,” Mueller said, “but this was built on being able to roll over the debt. As confidence deteriorated, all of a sudden, large lenders began to withdraw billions of dollars. Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers had to sell huge amounts of assets because they couldn’t pay the billions of dollars of short-term loans that lenders refused to renew.” With several major banks in crisis, the government stepped in with the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) to prevent large banks from failing.

Economists and laypeople have told four stories to explain the financial crisis, Mueller said. One story faults deregulation from the 1980s or 1990s; another points to greed and irresponsibility on Wall Street. A third hybrid story says that deregulation and the promise of government bailouts allowed Wall Street bankers to take on exaggerated amounts of risk. A final story invokes the Keynesian idea that the housing bubble was caused by an animalistic spirit of optimism rather than rational market-driven behavior.

None of these stories, Mueller reasoned, are sufficient to explain the causes of the crisis or to account for the extraordinary length it took our economy to recover. Mueller pointed to several specific regulations that “pushed financial institutions into making riskier bets.” For one, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates in the early 2000s for an extended period of time, which encouraged people to buy houses because they could borrow more cheaply, and encouraged banks to borrow more money because they could borrow more cheaply. Another factor was the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s efforts to lower lending standards. Out of a desire to open up the housing market to people with lower incomes, banks were encouraged to loosen established loan standards. Banks lowered the traditional 20 percent required down payment and allowed borrowers to take on monthly mortgage payments that comprised a large percent of their monthly income.

Mueller said that TARP, intended to heal the financial system, was itself part of the problem: “The government was creating legal and regulatory uncertainty because some banks were bailed out and others weren’t. The legacy this created was that it made markets less dynamic by subverting profit and loss signals.” The stock market was more volatile after TARP than before: eight of the ten days with steepest stock declines took place after the bailout program.

It’s impossible to speak confidently about “counterfactuals and hypotheticals,” Mueller said, but it is telling that the American economy’s recovery from the 2008 crisis was the slowest in history. While the 10 previous recessions in U.S. history were followed by 4.3 percent real annual GDP growth rates as the economy started to recover, GDP grew at only 2.08 percent annually after the 2008 recession. Had banks been able to follow profit and loss signals more directly, Mueller argued, recovery would likely have taken place much more quickly.

The ensuing conversation with David Bahnsen touched more on the moral dimensions of the financial crisis. Bahnsen asked, “From a Christian standpoint, do we view greater home ownership as a good that ought to be pursued at all from a public policy standpoint?”

According to Mueller, lowering lending standards in order to make home ownership accessible to more people does more harm than good, since a shift in the market can make it impossible for the borrower to continue making mortgage payments. “The best approach is encourage people to engage in productive activity and remove the obstacles to employment, to building low-cost apartments, to building houses.”

During the audience Q&A, Fritz Scibbe (Humanities ’21) asked if national student loan debt could ever take on the scale of the housing bubble. For Mueller, student loans carry a lower risk of affecting the whole financial system. “If there was a debt forgiveness program that suddenly affected 20 percent of those with student loans, that could cause a similar kind of shock to the market, but, overall, the risk is lower,” Mueller said. While housing is tied to a real asset with structural connections to other industries like construction, student loan debt refers to a past educational experience, making it more isolated.

Dr. David Tubbs asked about the history of housing bubbles, and Mueller said that the closest thing to the 2008 bubble was in the early 1990s, though there have been regional trends caused by the movements of large companies. Essentially, for a bubble to form, interest rates and borrowing need to be distorted from reality.

“Much of what we see in the housing market hasn’t been true historically,” Mueller concluded. “I challenge the story that deregulation got us into this mess because a lot of people don’t realize how many regulations and subsidies actually contributed to the problems they are trying to address.”