Dr. Steele Brand Launches New Book ‘Killing for the Republic’

Dr. Brand’s book launch addressed two questions: How did Rome survive after so many battle defeats? And second, why does it matter to us?

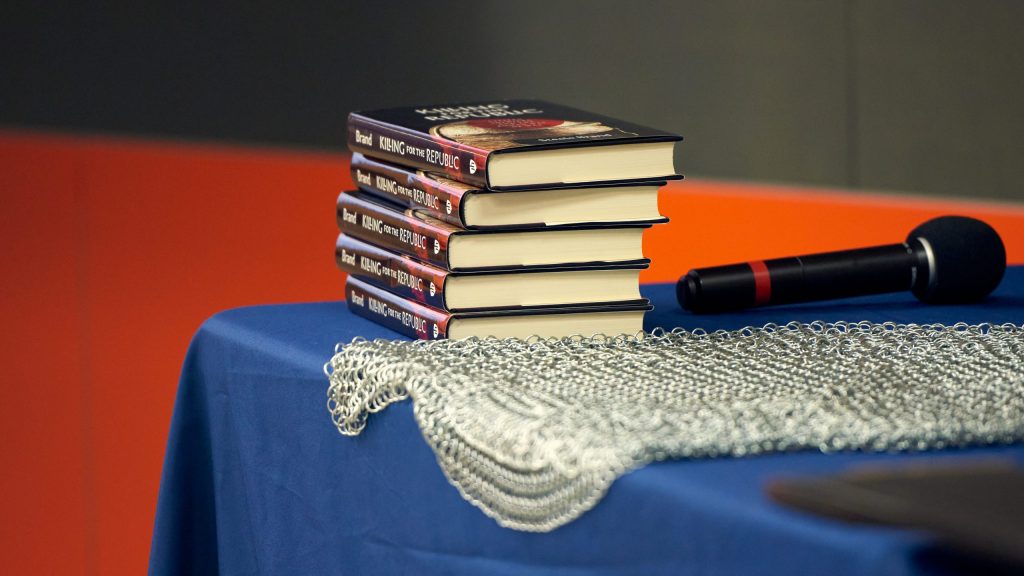

On Friday January 31, The King’s College hosted the launch of Dr. Steele Brand’s book, Killing for the Republic: Citizen Soldiers and the Roman Way of War (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019). Dr. Brand serves as assistant professor of history at King’s. He has also published articles in journals such as Religions and Humanitas about how this premodern ideal of citizen-soldiers has informed and inspired modern republics, particularly the United States.

Brand’s research focuses on the relationship between farming, citizenship, and soldiering. Constitutional polities—especially premodern, agrarian republics—cultivated a unique set of virtues and a deadly form of civic militarism that created tough citizens who were as involved in politics as they were proficient at defending their political system. His teaching explores how the public life of the spirit binds people together within a polity.

Brand opened the launch with two questions. First, how did Rome survive after so many battle defeats? And second, why does it matter to us? Brand started with a brief retelling of some embarrassing Roman defeats including the Battle of Cremera, the time the Gauls swooped down into northern Italy and chased off a Roman army before occupying the city, and the time the Samnites surrounded a Roman army and made them walk under the yoke of three spears as a humiliating sign of submission. Yet somehow, these defeats did not stamp out the Romans. Brand said, “As so many people discovered when fighting Rome, you can win battles but you can’t win wars because winning wars requires an indomitable public spirit.”

Brand shared an excerpt from his book, attributing this indomitable civic spirit to what he termed the “ethos of the farmer”:

The smallholder’s farm was the incubator for Roman moral, physical, and practical education. The home held the family’s hearth, before which they worshipped the ancestral gods. Piety and family devotion served as the basis for loyalty to the broader political community. . . . Until their mid- to late teens, when boys adorned the toga virilis as a sign of their manhood and responsibilities as a citizen, boys learned their family histories, acquired the literacy and mathematics necessary to conduct business transactions and the practical skills needed for fighting and campaigning, and absorbed the cultural mores of Roman society such as respect for authority, honesty, duty, and honor. Roman fathers were expected to instill discipline, frugality, industriousness, and self-reliance in their children.

Brand also attributed Roman resilience to their ability to borrow from their neighbors. Fritz Scibbe (HUM ’21), the burly president of the House of Reagan, modeled Brand’s collection of adoptive Roman war gear, including chain mail, a montefortino helmet, scutum (shield), the pilum (heavy javelin), and the gladius (iconic Roman sword). The Romans adopted these pieces from their enemies and then enhanced them. The Roman practice of finding inspiration from their enemies explains their victory at the Battle of Pydna in 148 BC: even during battle, the Romans were able to adapt whereas the Macedonian phalanx lost its cohesion and was unable to recover.

To the second question, Dr. Brand pointed to the strikingly Roman makeup of the United States system of government: mixed government, senate, popular assembly, age requirements, term limits, collegiality, checks and balances, agricultural republic, federalism, universal citizenship, public services, civic virtue, civic militarism. He shared the closing lines of his prologue:

[Americans] must also take seriously the ancient republics that educated their farmers. . . Unless they wish to dismiss historical models entirely, modern Americans must choose from which models they will learn. . . . If America seeks a future inspired by the virtues of its past, then it must not merely derive inspiration from the founders. It must look to the Roman Republic which inspired them.

Brand referenced Polybius, Sallust, Cicero, and Livy (among others), who “believed Roman civic virtue was what bound its unique constitution together, what allowed them to absorb devastating military defeats, what encouraged conquered peoples to be absorbed by and fight for Rome, and what produced a culture that demanded service and sacrifice from its leaders.”

Brand closed with discussion about “what went wrong.” To summarize the complex answer to that question, Brand offered a six word synopsis: uncontrolled militarism; constitutional stagnation; moral disintegration. In short, the Roman civic spirit, which had been the driving force, dissolved over time.

Brand offered several closing questions for the audience to consider. Can a republic live with civic virtue? Are all republics, including our own, doomed to die? How much of a republic are we if less than 5% serve in the military? Should you authorize a war and not fight in it? And, most importantly: If Rome was the best republic and it included all this killing and dying, what does that say about human government?