Liturgy: “Joseph made himself known to his brothers …”

In the wake of the deadly violence of Charlottesville, and the aftermath which has been of such great concern to us all, we greet this year’s liturgy with a renewed sobriety and a resolve to bring the love of Jesus to those whose god is the “blood and soil” of this world.

What is the King’s Liturgy? King’s Liturgy defines our experience together as a Christian community. It outlines the rhythms we celebrate with the Church at large: Scripture readings, Sabbath habits, and celebration of Holy Days and historical events.

This Week’s Lectionary Readings

Genesis 45:1-15

Psalm 133

Romans 11:1-2a, 29-32

Matthew 15:10-20, 21-28

This week’s liturgy is contributed by Dr. Gregory Alan Thornbury, President of The King’s College:

In the wake of the deadly violence of Charlottesville, and the aftermath which has been of such great concern to us all, we greet this year’s liturgy with a renewed sobriety and a resolve to bring the love of Jesus to those whose god is the “blood and soil” of this world. The death of Heather Heyer, at the hands of an enraged neo-Nazi, awoke us from our summer slumbers. The evils of white supremacy, fascism, and an ideology of hate have always been there, of course, churning just below the surface of media attention. Those of us in the racial majority have largely chosen, sinfully, to ignore the crisis.

In the midst of these horrors, we have the witnesses of peace. Among them are Heather Heyer’s parents. At her funeral, her father, Mark Heyer, voiced what the nation needed to hear: “She wanted to put down hate, and for my part, we need to stop all of this [violence], and forgive each other. That’s what the Lord would want us to do.”

Of course, it’s not that easy. Love in the face of escalating violence and hatred requires more than a tweet or a press release. It’s the hard work of daily acts of self-abnegation in love to the Other—our enemy. It requires Sermon on the Mount levels of dedication.

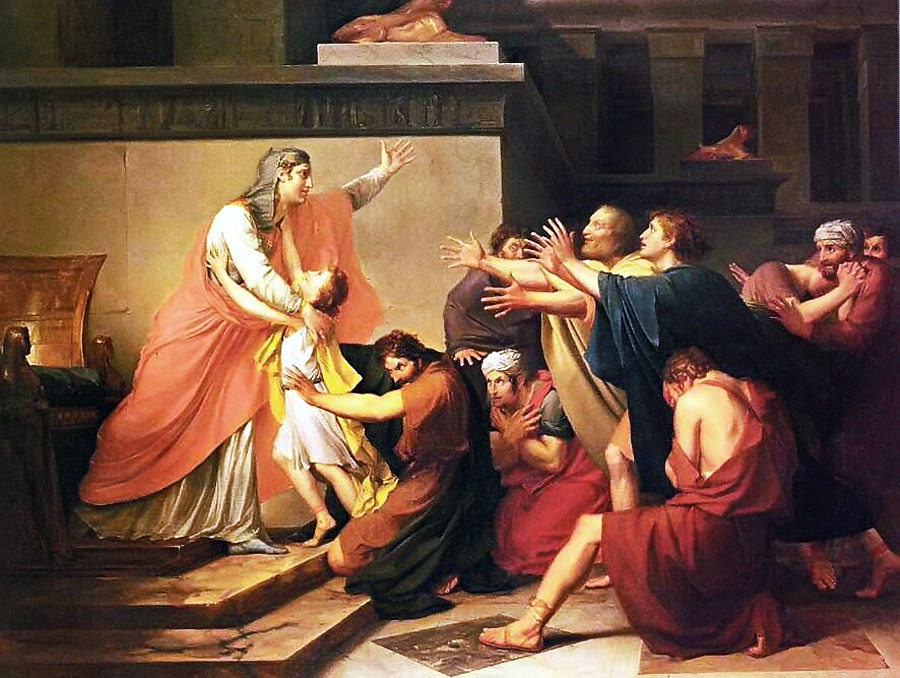

In Genesis 45, we see how the cycle of violence is finally broken between Joseph and his brothers. We remember from the story that Joseph’s brothers initially wanted to kill him out of their contagion of envy and jealousy—due to the disproportionate amount of fatherly love poured out upon him. Thankfully, Reuben prevailed upon the rest of the brothers to only simulate his death, but they still attack him, sell him into slavery, and, for all intents and purposes, leave him to die.

Once in Egypt, Joseph is made the scapegoat again—this time for a crime he didn’t commit—by Potiphar’s wife. Once again, he is left to die – this time in prison. Through semi-miraculous circumstances, he escapes—largely because he practices divination—he can interpret the dreams of Pharaoh for the nation. As a seer, he forecasts a coming famine, and subsequently Joseph is elevated to a position of power—essentially that of vizier, or prime minister.

When Joseph’s brothers come hat in hand and desperate to survive the famine in Canaan, they of course do not recognize Joseph, who is fully Egyptian. In disguise, Joseph tests his brothers’ tendency to renew the cycle of violence and the blame game. When Joseph sets up his youngest brother Benjamin to look like a thief, his brothers could have once again accused the boy whom their father Jacob loved best, and returned with their lives and fortunes intact in the midst of famine.

Remarkably, this time it is Judah who does the unexpected. Instead of pointing fingers at his brother Benjamin, he asks to take the blame for any wrong done. In doing so, he volunteers to be the victim himself. Judah is ready to give up his own life to preserve that of another brother; he is willing to die rather than break his father Jacob’s heart.

As the philosopher René Girard has observed, it is at this moment that the “spell” of mimetic rivalry and violence is broken. The system of hatred—brother against brother—is halted by an act of self-sacrifice. This prompts Joseph to reveal his identity to the brothers. For once, everybody wins. Everybody is saved. Everybody lives. It is an image that presages the ministry and sacrificial death of Jesus.

Although I admire Girard’s writings on these issues, he does not understand fully the meaning of the power that comes from the cross of Christ in the gospels. Yes, Jesus exposed the scapegoat mechanism that results from envy and violence, but he did something far greater. He provided himself as a substitute, he took our place at Calvary, he bore all the sins of the world upon his shoulders.

Why is this important? Because the cross truly does set things right. It gives us access to the power of the Holy Spirit, which in turn gives us the power to oppose every form of satanic violence among the principalities of this world.

We must, like Joseph, make ourselves known to one another in this community. We must reveal our lives of hurt, pain, and for some in our community, true victimization. In so doing, we must covenant to stop the worldly cycle of envy, jealousy, bickering, backbiting, rumormongering, and, yes, hate. These are the things that characterize the world. They cannot—and must not—be known among us as we start this year together as a communion of saints at The King’s College. And just who are the saints? Just think of the stained glass. They’re the people the light shines through.