Liturgy: “Not for Children”

God cannot be tamed, made safe for children, forced to fit our theories. To quote a priest from the classic football film Rudy: “Son, in thirty-five years of religious study, I have only come up with two hard incontrovertible facts: there is a God, and I’m not him.”

What is the King’s Liturgy? King’s Liturgy defines our experience together as a Christian community. It outlines the rhythms we celebrate with the Church at large: Scripture readings, Sabbath habits, and celebration of Holy Days and historical events.

This Week’s Lectionary Readings

Job 38:1-7, 34-41

Psalm 104:1-9

Hebrews 5:1-10

Mark 10:35-45

This week’s liturgy is contributed by Dr. Ethan Campbell, associate professor of english and literature:

As the father of two young kids, I’ve spent hundreds of bedtimes reading stories from children’s Bibles, and I’m always curious to see which parts they leave out. Sodom and Gomorrah always get the axe; David fights Goliath, but doesn’t cut off his head; Jesus’ miracles omit the shrieking demons. Even my son Jonah’s favorite story, about his namesake, focuses on the whale and leaves out the worm that drives Jonah to rage.

In every children’s Bible I’ve seen, the Book of Job also gets left on the cutting room floor. Job is one of my favorites, but it’s easy to see why well-meaning publishers might try to keep children away. Satan roams the earth, and masses of people are slaughtered by sword and cyclone. There’s a man covered with running sores, a shrewish wife, holier-than-thou friends.

But I wonder if the real reason this book gets censored is for what God does. Just listen to what he says in this week’s reading from Chapter 38, in response to Job’s understandable request that God give an explanation for his suffering:

Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundation?

Tell me, if you understand.

Who marked off its dimensions? Surely you know! (NIV)

Normally I like to quote biblical poetry in the King James Version, but in this case, the 17th-century language blunts the tone to our ears. These lines are dripping with sarcasm, of a kind I cringe to think I’ve used in arguments myself. They say, in effect, “You wouldn’t understand, so shut up.” This tone almost never comes across as loving, and since we know God loves people, his words might sound out of tune to us.

They also don’t exactly answer Job’s original complaint. At least, they don’t answer it in a logical way. God’s point is impossible to refute—Job wasn’t, in fact, present at the moment of creation. But the problem of evil and suffering isn’t magically resolved with a reminder of our ignorance. As a skeptical character in Charles Williams’s novel War in Heaven puts it, “As a mere argument there’s something lacking perhaps in saying to a man who’s lost his money and his house and his family and is sitting on the dustbin, all over boils, ‘Look at the hippopotamus.’” But God isn’t presenting “a mere argument.” In fact, he’s not making an argument at all.

What he is doing, first of all, is giving Job exactly what he needs. After a few chapters of the most stunning poetry ever composed, Job will be on his face in worship. But God is also giving Job, and us, a revelation about himself and the nature of his world.

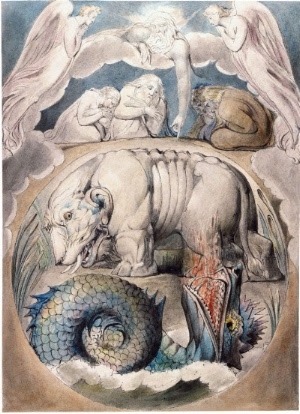

Though God commanded mankind to rule the earth (Genesis 1:28-30), there remain parts that cannot be subdued, that belong wholly to God, and he runs through a list in lavish physical detail—a pride of lions, a wild ox, a war horse eager for battle, an eagle feasting on blood, Leviathan. God delights in these creatures simply because they give him pleasure, and when he says, “Behold,” the only response we can have is to look.

Here is the poet Stephen Mitchell’s rendition of 41:1-8:

Will you catch the Serpent with a fishhook

or tie his tongue with a thread?

Will you pass a string through his nose

or crack his jaw with a pin?

Will he plead with you for mercy

and timidly beg your pardon?

Will he come to terms of surrender

and promise to be your slave?

Will you play with him like a sparrow

and put him on a leash for your girls?

Will merchants bid for his carcass

and parcel him out to shops?

Will you riddle his skin with spears,

split his head with harpoons?

Go ahead, attack him:

you will never try it again.

The KJV concludes: “Who then is able to stand before me?”

This is not an argument—it is a proclamation. God cannot be tamed, made safe for children, forced to fit our theories. To quote a priest from the classic football film Rudy: “Son, in thirty-five years of religious study, I have only come up with two hard incontrovertible facts: there is a God, and I’m not him.”

On second thought, maybe this is a story we should be telling our kids.