December 2016 History Spotlight | Northeastern Bible College: Christ for Everyone

Our series of campus histories takes a detour from King’s to examine the story of Northeastern Bible College—its location, its educational mission, and how it came to play a pivotal role in helping King’s reopen in New York City, becoming part of the King’s community in the process.

Dr. Charles W. Anderson, a conservative Baptist pastor and leader (and friend of Percy Crawford), opened a three-year Bible school at the church he pastored in Bloomfield, New Jersey in 1950. Anderson had witnessed the effects on missionary work of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy that had dominated theological circles and echoed outward in churches nationally in the 1910s through the 30s, and was committed to strengthening Bible knowledge and the missionary activities of the American church. He also had a vision to see churches planted and Christians drawn to the greater New York area. His church—one of the largest in northern New Jersey at that time and very missions-minded itself—was called Brookdale Baptist Church, and the school was called Northeastern Bible Institute.

The school underwent two name changes, becoming Northeastern Collegiate Bible Institute in 1964 upon adding a four-year program, and Northeastern Bible College in 1973. We will use the last name throughout this article for clarity’s sake. Long before the name change, though, Northeastern outgrew its quarters at Brookdale Baptist Church and purchased its own educational space.

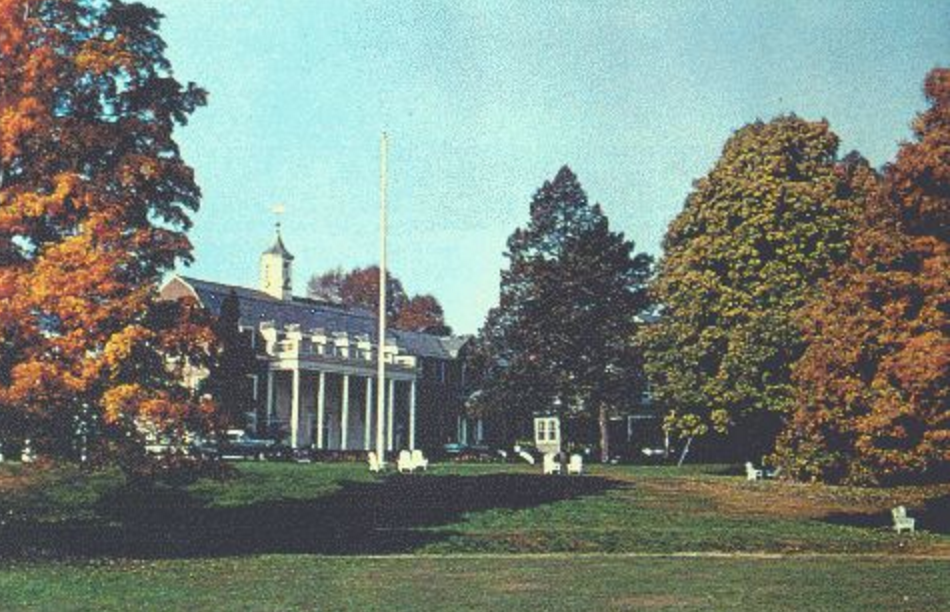

The campus in Essex Fells where Northeastern spent most of its life was about five miles west of its first site in Bloomfield, as the crow flies. It had first belonged to a preparatory day and boarding school for boys called the Kingsley School, which opened there in 1900. It was named not for its founder or headmaster, but for an English author, philosopher, and clergyman named Charles Kingsley—with whom, however, the headmaster was personally acquainted. The central building that became Northeastern’s Whittle Hall dates from the Kingsley days. The Kingsley School drew students from all over the world and boasted “unusually homelike” dormitory rooms for the boys.[1]

After the Kingsley School, the campus went to a girls’ preparatory school—the Montrose School for Girls of Montrose, Pennsylvania; later still, the U.S. Army used the campus as a training ground for cadets in 1945.[2]

The dates and details of these transitions were not available in time for publication. What we do know is that Northeastern purchased the campus in 1952 and enjoyed a long residence there until 1990. Dr. Anderson also enjoyed a long presidency, from the school’s founding in 1950 to 1980. In order to receive accreditation, Northeastern had to offer a liberal arts course, which was one of its available programs; but it was not, like King’s, a traditional liberal arts college. Nor was it, like Nyack, a denominational school. It was, even more emphatically than King’s, a school for training pastors, missionaries, and laypeople for Christian service; and it was the only independent Bible school in the northeast. If King’s aspired to be the Wheaton of the east, Northeastern functioned like the Moody Bible Institute of the east: The school’s academic offerings were structured so that all students majored in Bible by default, and then chose other areas of study such as pastoral studies, missions, and the like, in which to concentrate or emphasize. It offered two-year degrees, four-year degrees, and a Th.B. that was mostly geared for pastors and teachers in nearby regions who wanted to deepen their knowledge.[3]

Dr. Mitch Glaser ’74, president of Chosen People Ministries, describes Dr. Anderson as a strong leader, tested and tried through the theological controversies of the time and a denominational split that took place between northern and southern conservative Baptists. Without knowing anything else, one might expect Northeastern to be a place where doctrinal and intellectual uniformity was valued and enforced, but this was not so. Dr. Anderson was himself a leader in the post-World War II dispensationalist tradition, and taught a course on dispensational theology. Other faculty members held a variety of theological opinions. Dr. Stan French, who taught prophetic theology, was a covenant theologian. Dr. Wesley Olson, a five-point Calvinist, taught systematic theology, and Dr. Gordon Olson was a four-point Calvinist. Such a lineup of professors meant that students were exposed to all of the various opinions on a variety of issues, all the way up to and including the end times.

The student body was also not all cut from the same cloth. During the 1970s, the Jesus Movement on the West Coast reached and brought into the church hippies and ex-hippies in large numbers, and generated an important recruiting constituency for Northeastern. The end of the Vietnam War provided the school with an influx of veterans, coming on the GI bill. Both of these groups tended to be a bit older than the traditional college student, and to have a different perspective on life. But then, of course, there were also the traditional college students who came from Christian families and often had grown up in the area. Northeastern also attracted a large number of missionary kids and international students. It was a diverse milieu, and even conservative Northeastern was not immune to the turbulence that swept America in the 1970s. Still, the school’s priorities came across: Northeastern served 4,200 students,[4] and 70 percent of its graduates are, or were, engaged in full-time Christian service.[5] Northeastern received full accreditation from the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools in 1974.[6]

When Dr. Anderson retired in 1980, Dr. Gordon Henry came on as president. Dr. Mitch Glaser, who joined Northeastern’s board in the 1981-82 academic year, recalls that Dr. Henry was a good man, but he was used to the more Christian climate of the south and had some difficulty adjusting to the more secular northeast, particularly where fundraising was concerned. He was succeeded in 1984 by Dr. Robert Benton, also a good man whom Dr. Glaser described as a “gentle soul.” Northeastern had a new building at this time that had required a mortgage to build, which became a major part of the financial difficulties that were beginning to arise for the school. There were no scandals during this time and everyone worked hard; the professors, students, and programs at Northeastern were as high-quality as ever. But the Jesus Movement was fading and the supply of veterans was dwindling, and the disappearance of these two recruiting constituencies proved too difficult for the school to navigate. As a 1999 New York Times feature on what became of abandoned campuses in the northeast notes, more and more students were going to college during this time, but it meant that schools had to compete harder and harder for them.[7] Dr. Glaser observed that for parents wanting to send their children to a Christian college, the northeast was simply not the most attractive destination, adding that the same dynamics affected The King’s College, which was facing up to its own difficulties at the same time in Briarcliff Manor.[8]

Dr. Jim Bjornstad, a former Northeastern student and professor, came on as president in 1987 as a sort of “favorite son” of the school who might be able to stem the tide of decline. It was too late, however, and Northeastern had to begin selling pieces of its campus to attempt to get a handle on its debts. This proved impossible, and the campus closed in 1990—a process that, according to Dr. Glaser, was slow and difficult, as students had to be transferred, records kept, and properties sold.

The board of trustees had a dissolution clause in its by-laws that kept the board from dissolving until the institution’s assets were given to a like-minded organization. Several institutions were in the running for this gift, and it was a difficult decision. But the opinion that prevailed was that, if at all possible, the money should go to a college ministering in the greater New York area. When King’s came on the scene through Stan Oakes and Friedhelm Radandt, many meetings and discussions, as well as the presence of a matching grant, convinced the board that it would be a good fit. King’s “seemed willing to take over records, transcripts, and alumni contact, and to keep the embers of God’s work at Northeastern alive,” Dr. Glaser said. He kindly added that he feels King’s has always done its best to keep its part of the bargain, part of which was maintaining a course of study in Bible or theology.

The last land parcel from the Essex Fells campus was contracted for sale to someone who planned to build a rehabilitation center on it, but residents objected because they believed this plan would overdevelop the land and interfere with their quality of life. In the end, the land was purchased by the town of Essex Fells. [9] It now contains some housing and a lot of park land with athletic facilities. The basketball courts remain, and Dr. Anderson’s home has been sold as a private residence. [10]

Northeastern Bible College has an honorable history and an amazing legacy of dynamic Christian service around the world; it was indisputably a place where the Spirit of God changed lives. Dr. Glaser said, “Even though I was going to a church, Northeastern was my spiritual family.” He described the chapels as dynamic and the school’s annual conferences as formative and deeply powerful. “There was a spiritual tone there that’s hard to recapture,” he said. Northeastern’s closing gift to King’s was a great honor, not only because of what it enabled The King’s College to do, but because it meant that all of Northeastern’s alumni came under the King’s umbrella and became part of its community.

We are thankful for Northeastern’s history, legacy, and role in our community, and that the friendship of Dr. Charles Anderson and Dr. Percy Crawford lives on in an institutional unity that most likely neither of them ever envisioned. Next month, we will look at the history of the Empire State Building where The King’s College established its first foothold in New York City, and the remarkable, divinely-orchestrated events that brought about its reopening.

[1] Poekel, Charles A., Jr. West Essex, Essex Fells, Fairfield, North Caldwell, and Roseland. “Images of America” series. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 1999.

[2] Poekel.

[3] Phone interview with Dr. Mitch Glaser, December 12, 2016.

[4] The King’s College Registrar.

[5] Wikipedia: “Northeastern Bible College.” Accessed December 16, 2016.

[6] Wikipedia: “Northeastern Bible College.”

[7] Garbarine, Rachelle. “For Abandoned Campuses, Recycled Lives.” The New York Times, Sept. 8, 1999. Accessed December 16, 2016.

[10] Glaser interview, and email correspondence with Byron Elliot, June 17, 2018. Elliot writes, “My wife and I live in ‘the President’s home’ that Mr. Anderson and several students/missionaries/voluntee